War [in Ukraine] is a Racket [for Russia]

How Russian businessmen are using Telegram to organize the theft and transport of Ukrainian agriculture

Highlights from today’s post:

How war crimes get a technological boost from an unexpected source: Telegram

A new type of misery visited upon Ukraine: Agricultural theft

Before we get into today’s post, do you need to convert geo coordinates into useful location information?

This week's edition is sponsored by OpenCage who operate a highly available, simple to use, worldwide, geocoding API based on open data. Try the API now on the OpenCage demo page.

A few weeks ago, the mayor’s office of Nikopol, Ukraine posted a video of what appeared to be trucks loaded with stolen Ukrainian grain driving towards Crimea. Emblazoned on the side of these vehicles was the Russian military’s distinctive “Z” insignia.

Among the many atrocities experienced by the Ukrainian people, thefts like these have lately been in the spotlight. Russian businessmen, supported and escorted by Russian armed forces, have been wholesale stealing wheat, corn, soybeans, and other crops from granaries and warehouses across occupied Ukraine.

As I found, the popular messaging platform Telegram has been central to these efforts.

I scraped several of Russia’s most popular farm sales, logistics, and transport Telegram groups. I parsed their posts and discovered a disturbing trend. Dozens of Russian freight forwarders and agricultural merchants use Telegram to request bids for truck drivers to pick up massive amounts of Ukrainian crops and bring them back to Russia.

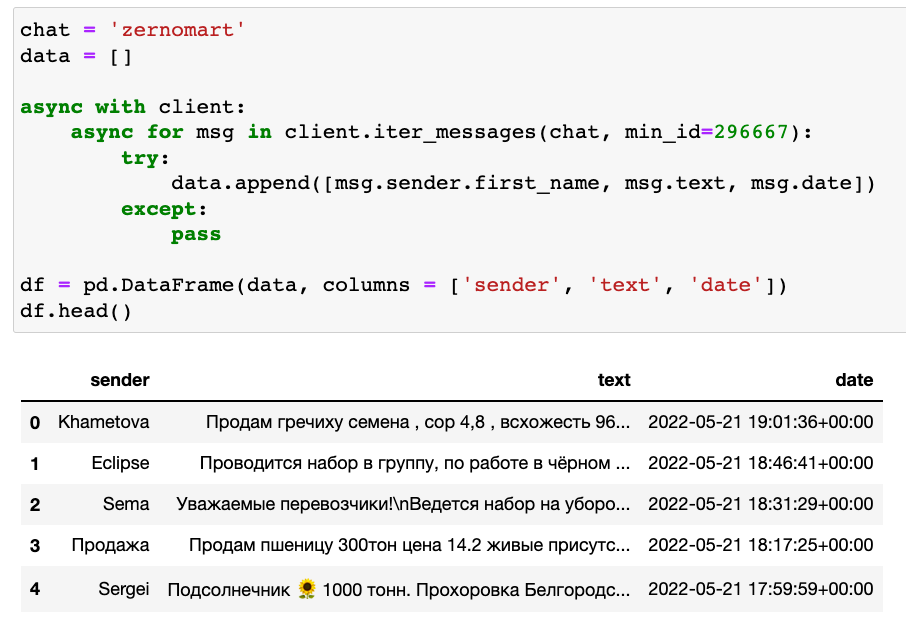

For anyone who wants to check my work, here’s my code. I used Telethon to connect to the Telegram API, select any message in the farming groups after the date of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and download the message’s text, timestamp, and the first name of the sender to a table.

I repeated the process for each of the six groups I examined and built a massive table containing thousands of lines, each representing a message in a Russian agricultural Telegram group.

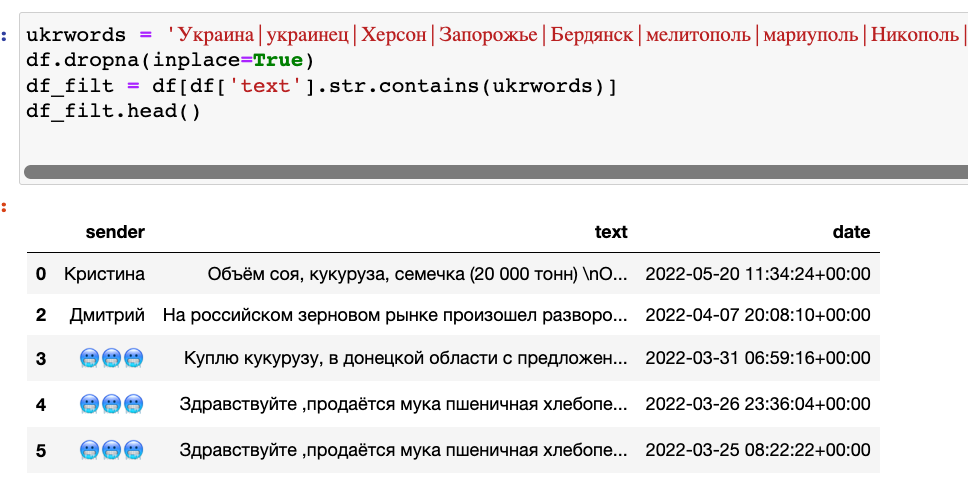

From there, it was a simple matter of filtering down the messages to only those that contain Ukrainian keywords or place names.

To be sure, there were a few false positives, such as news articles about Ukraine that people posted in the groups. But the vast majority of the 242 remaining messages were Russians offering to buy or sell Ukrainian crops or people attempting to arrange transport for these crops to Russia, although the final destination of these crops is ultimately unkown.

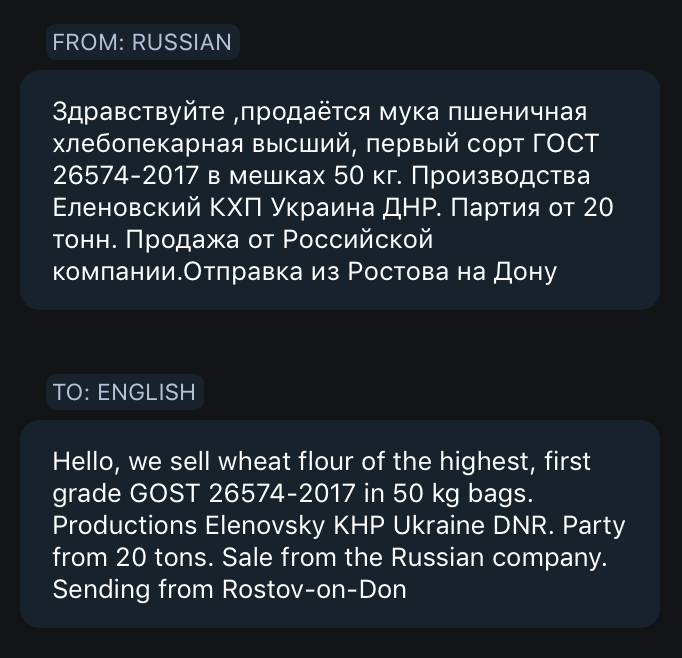

Some of these people were trying to export crops from legitimate businesses in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. One user, with the helpful username “🥶🥶🥶”, wanted to export 50-pound bags of wheat flour from the Elenovsky bakery in Olenivka, Donetsk Oblast. However, a search of his posting history shows that he’s been trying to do so since February 10th - well before the start of the war. In all likelihood, 🥶🥶🥶 is therefore doing nothing wrong.

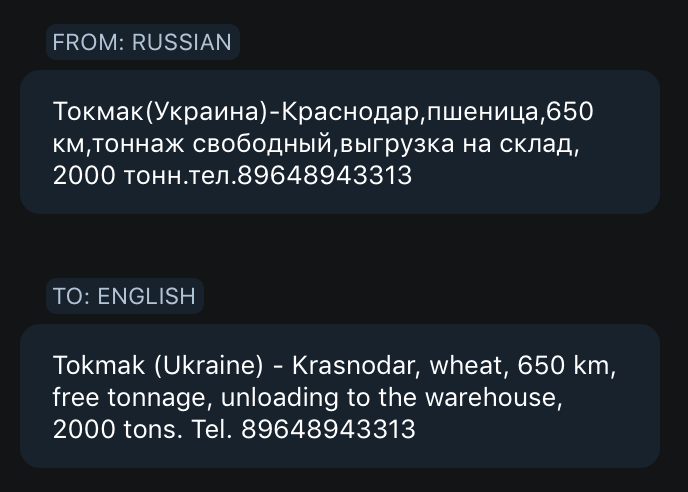

But other posts raise questions. One grain merchant, Evgeny, has quite a few posts in these Telegram groups from before the war. However, virtually all of his pre-war posts asked for drivers interested in driving the Crimea-Stavropol or Crimea-Krasnodar routes1. Then, on May 10, he asked for his first Ukraine route: to take a 2,000 ton shipment of wheat from Tokmak, Ukraine to Krasnodar, Russia.

Russian soldiers captured Tokmak on March 7 and, by early May, the town and surrounding region were firmly under Russian control. Did Evgeny just luck out on his first Tokmak contract less than two months after Russia took over? Or was his 2,000-ton shipment part of the “grain and sunflower seeds” being removed from the region by Russian forces?

Other requests were more clinical. This fellow, Ivan, requested drivers for two routes. One was a pretty unremarkable 82-kilometer trip to transport 20 tons of corn within Voronezh, Russia. The other was a curt request for bids on a massive shipment of corn, soybeans, and seeds from Kherson, Ukraine to Crimea.

To give a sense of the enormous scale involved, Ivan’s request was for a 20,000-ton shipment. CNN reported that one Russian ship allegedly responsible for taking stolen grain from Crimea to Syria has a capacity of 30,000 metric tons. In other words, the grain involved in Ivan’s single request could fill two thirds of a cargo ship2.

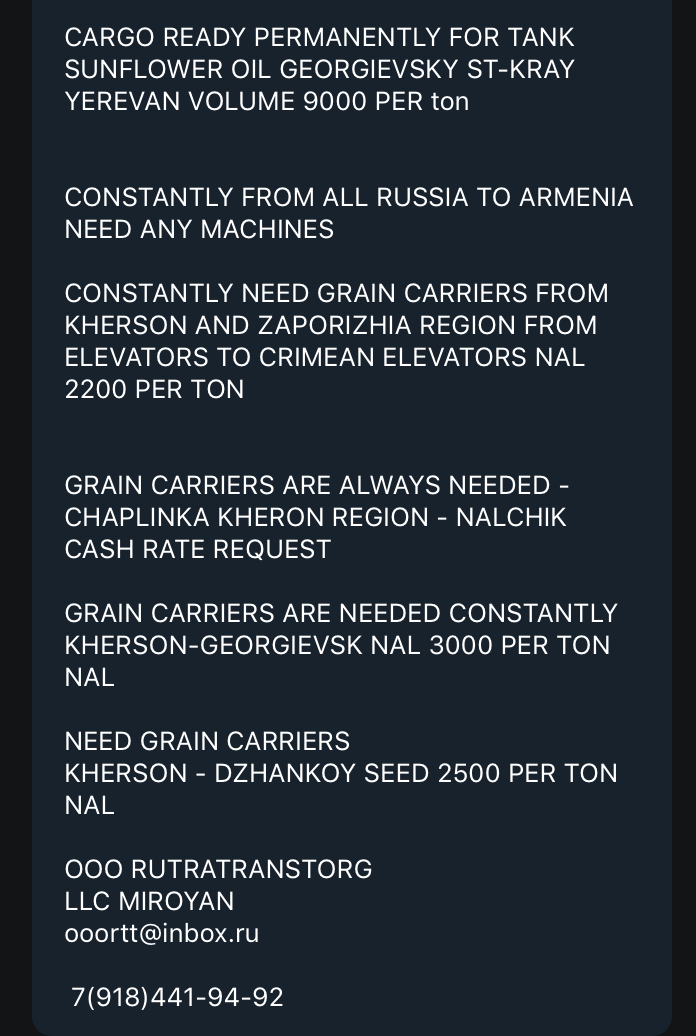

Other requests were more blatant. One Russian company, RTT, blasted out a call for 50 trucks in late April to transport grain from several locations, including Vasylivka in Ukraine’s Zaporizhia Oblast, to an elevator in Dzhankoy, Crimea.

Since Russia took control of Vasylivka in early March, locals have noticed Russian forces stealing tons and tons of grain from warehouses across the region.

Translation: “Russian soldiers are massively exporting grain from the temporarily occupied territories of the Zaporizhia region. Russians removed 1,200 tons of grain from the territory of the mechanized granary of "Blagoveshchensky Grain Product, LLC" in the Vasylivka district of the Zaporizhia region”

Later in May, the same company put out another call for even more routes. This time, they requested grain trucks to drive between Enerhodar, Melitopol, Svatove, Chaplynka, Kherson, and Zaporizhia, Ukraine and several locations in Russia or Crimea. Russia occupies all of the Ukrainian regions for which RTT requested drivers.

To drive home the spatial relationship between these agricultural loading points, here’s a map of all the locations mentioned in this article overlaid onto territory that Russian and pro-Russian forces control in Ukraine.

Finally, these trips command a premium. Agricultural shipments within Russia were usually advertised for a few hundred rubles per ton (often hovering around the 600-700 rubles per ton mark). Shipments between Ukraine and Russia or Crimea were advertised for several times that.

Rates for these cargoes hit 1650, 2000, 2200, 3000, or sometimes even up to 4200 rubles per ton. Plus, sellers offered additional incentives like cash payments, VAT avoidance, advances, pre-payment, and paid expenses for the journeys.

So what does this all mean? It offers a more banal but no less horrifying Russian rationale for the war. The Russian government maintains they invaded Ukraine to remove “Nazis” from power. As wrong as that may be, it’s undoubtedly powerful motivation. But what if, given everything above, others are simply using the war as a get-rich-quick scheme?

Separately, one of the main criticisms of the West supplying and arming Ukraine is that arms transfers represent a no-questions-asked giveaway to defense companies, who already rake in ludicrous profits. Perhaps true, but it also appears that Russian businessmen, supported and escorted by Russian armed forces, are lining their pockets in the exact same way.

On this point, it’s worth quoting Smedley Butler — Marine Corps general, two-time Medal of Honor winner, and outspoken anti-war advocate — in full.

War is a racket. It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives. A racket is best described, I believe, as something that is not what it seems to the majority of the people. Only a small 'inside' group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few, at the expense of the very many. Out of war a few people make huge fortunes.

From the ports of Crimea, to the wheat fields of Kherson, to the railroads of the Donbas — war is a racket.

I’d like to extend a massive thank you to to Tom Bullock, who provided invaluable thoughts, comments, and ideas for further exploration (👀) for this piece. Give him a follow if you haven’t done so already!

Both Stavropol and Krasnodar are cities in southern Russia.

Roughly…because I’m not sure if the Russian shipments are measured in short tons, long tons, or metric tons.

This is truly impressive, RC. Great to speak briefly with you over Zoom today during our Substack seminar.

Brilliant stuff.