Before getting into today’s post, I want to shout out a tool built by Github’s tg12. It scrapes the web for system backups, databases, spreadsheets, passwords, and other leaky data just left on the internet for the world to see. The tool itself isn’t ready for public consumption quite yet but the first set of scraped files is on the linked GitHub repository for folks to trawl through. I’ve taken a quick spin and there are certainly some cool leads there. If that piques your interest, take a look yourself and let tg12 know what you find!

Anyway, some stuff came up last week and I didn’t have enough time to work on a really cool piece that I now hope to share with you all in two weeks. Plus there was just a lot happening on my end at home and at work. Shit happens. So let’s look at some cool satellite pics huh?

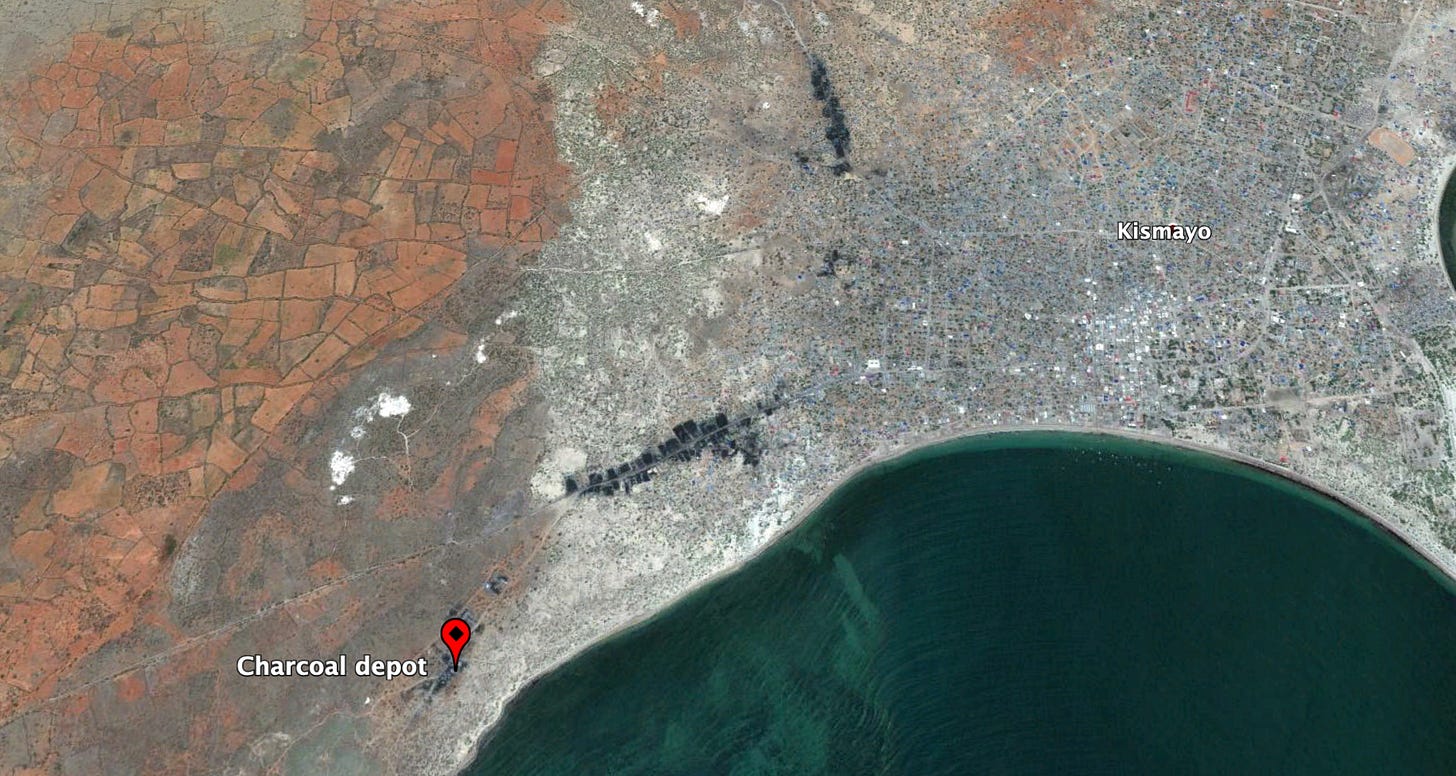

I was playing around on Google Earth the other day and I noticed something weird in southern Somalia. Virtually every port town south of the capital, Mogadishu, has these weird black smudges somewhere within city limits.

What in the good lord is this1.

Turns out the black marks are charcoal depots. The charcoal industry in southern Somalia has gotten quite a bit of news, NGO and government attention recently (not to mention attention from al-Shabaab and the AMISOM forces currently battling it out in Somalia).

However, attention has primarily focused on where the charcoal comes from and where it goes. Wood for charcoal is cut and burned at charcoal camps far inland, often resulting in severe deforestation, before being trucked to the coast and shipped to markets in the Persian Gulf, where the long-burning, high-quality Somali charcoal is used for hookah smoking.

Much less attention has been paid to the liminal spaces of the charcoal industry - namely, where the charcoal is stored, waiting for shipment to end users. I could only find a single paper that analyzed charcoal storage sites. As harsh as charcoal production has been for Somalia’s environment, charcoal storage has also wreaked havoc on the country’s landscape.

Using Google Earth and the paper linked above, I identified at least 12 charcoal storage sites across southern Somalia in locations ranging from cities like Kismayo to tiny villages like Buur Gaabo. Unfortunately, Google Earth images were, in many cases, several years out of date, preventing an updated analysis of some smaller depots.

These charcoal storage sites stick out for two reasons. First, as I mentioned above, the land around them is stained black. This coloring is likely due to the open topped bags used to store charcoal during transport from production sites to storage sites. As the bags get unloaded from trucks, bags will split or bits of charcoal will fall out, staining the ground.

The second reason is the bags themselves. I have no idea where these bags come from but for some reason, all charcoal produced in southern Somalia is stored in these greenish-teal sacks.

Credit: Reuters/Feisal Omar

There are so many sacks at charcoal storage sites that they can be seen from space, as in this 2012 image of the depot in the port city of Baraawe.

Based on the area of blackened land at most sites and the number of bags within them, charcoal production and storage seems to have peaked around 2015 but has remained stubbornly persistent since then.

Let’s zoom in on the city of Kismayo. In this 2006 image, charcoal depots blanketed the western half of the city (yes, most of those black smudges are from charcoal).

By 2012, the depots had consolidated to three main areas, still on the western side of the city, but each containing far more charcoal than any of the smaller, more distributed locations held in 2006.

Note that each of these three locations lie on a major route into the city. The southernmost one lies on the road leading to the city’s airport, the middle one lies on a small road to the city’s agricultural areas, and the northern one lies at the intersection of two roads heading inland to southern Somalia’s main charcoal-producing camps.

At each depot, traders could easily dump their loads of charcoal but, more importantly, whoever controlled the town (al-Shabaab until 2012 and Kenyan forces thereafter) could levy taxes on the charcoal coming into the city.

A few years later, the middle depot had reduced in size, but another storage location had popped up, this time just outside the city on a small coast road leading to a beach.

This is where some information about charcoal shipping in Kismayo is helpful. Historically, charcoal had been shipped out of the city’s port itself, as shown in this 2012 image of dhows lining up to export charcoal from Kismayo.

But, starting in 2014, satellite images show a tiny facility on the beach near the new charcoal depot started to get more use. This facility was built sometime between 2005 and 2010 but doesn’t appear to have been used for charcoal export until 2014. In fact, the first image showing charcoal being exported from the new facility (below) is also the first image in which the new depot appears.

Even more interesting is that the new port facility is less than a quarter mile away from the new depot. As soon as that depot was built, bags of charcoal started appearing on the nearby beach, ready for onward shipment and undeterred by recent construction at the shipping facility.

The facility, however, is not a port by any stretch of the imagination. It doesn’t have any docks, vehicles, or cranes and, until 2018, was only a glorified fence surrounding a small hut. These rudimentary facilities likely mean that only small boats can load charcoal there. Whether that means the small boats are transporting the charcoal to larger ships offshore, trying to avoid port taxes by not using Kismayo’s official port, or simply transporting charcoal up and down Somalia’s coastal waters to other ports is unclear. Nonetheless, Kismayo does appear to have two competing ports: an official one for everything a town needs to bring in and out (plus some charcoal), and an unofficial one used exclusively for shipping charcoal.

But what about the Kismayo depots themselves? How have they changed since the DIY port opened for business? In short, they’ve shrunk.

In fact, the three original depots declined as the new depot (and the associated shipping facility) expanded. The Sentinel-2 time-lapse GIF below shows the original charcoal depot on the road to the airport shrink from over 1000 meters long in 2016 to less than 600 meters in 2021.

Meanwhile, a similar time-lapse GIF of the new depot shows it staying roughly the same size from 2016 to 2021. (Note also the construction of the shipping facility toward the bottom and the severe deforestation and desertification near the coast).

A late 2020 birds-eye view of the city shows one of the original three depots has disappeared entirely while the other two are significantly diminished. The new one, on the other hand, remains the same size (not including the auxiliary charcoal storage near the beach and anything that may be stored in the new buildings constructed by the illicit charcoal port - both of which would increase the amount of charcoal able to be stored at the new site).

It’ll be interesting to see how charcoal depots (and their associated facilities) pop up and disappear throughout Somalia in the future. For now, although charcoal production and shipment may not be at mid-2010s levels, it’s clear that charcoal storage leaves an indelible mark on the country’s landscape.

All images credit of Google Earth, except where noted.