Morocco's Missiles

Analysis of drone strikes in Western Sahara shows Morocco is using Chinese-made missiles to allegedly target civilians and Polisario militants alike

Highlights from today’s post:

Background information about the Blue Arrow 7 air-to-surface missile

Open-source evidence from explosion sites in Western Sahara

Analysis that demonstrates Morocco is using Chinese-made missiles to fight the Polisario

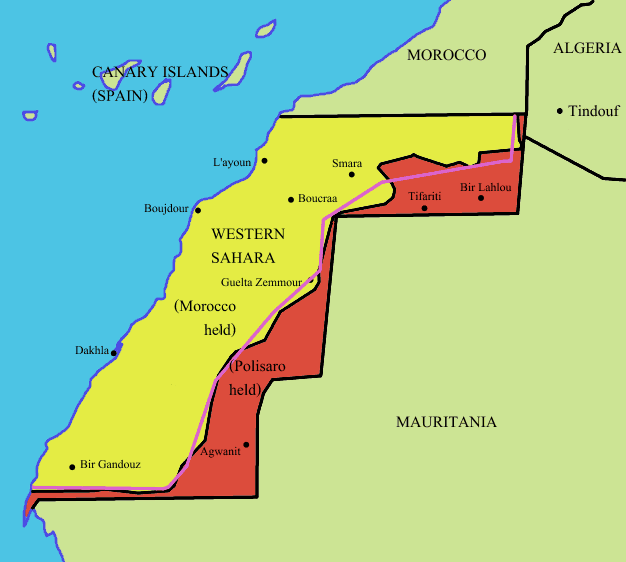

In the wide open desert of Western Sahara (a disputed territory that lies between Morocco, Algeria, and Mauritania), a conflict is simmering. Though the Moroccan army has long been at odds with the Polisario Front1 - a group in favor of self-determination for Western Sahara - the conflict between the two sides has escalated in recent months.

In a dangerous turn of events for the region, Morocco has begun deploying drones and drone strikes against Polisario fighters. In-depth analysis of the remnants of these strikes shows Morocco is using Chinese-made Blue Arrow 7 missiles to target the Polisario (according to Morocco) and civilians (according to the Polisario).

As this excellent Oryx article explains, Morocco has fielded drones for quite some time. However, the most recent spate of strikes - starting in April 2021 - appears to be Morocco’s first use of armed drones on the battlefield. Now, for the first time, evidence has surfaced that confirms Moroccan armed forces are using Blue Arrow 7 missiles to conduct these strikes.

What is the Blue Arrow 7?

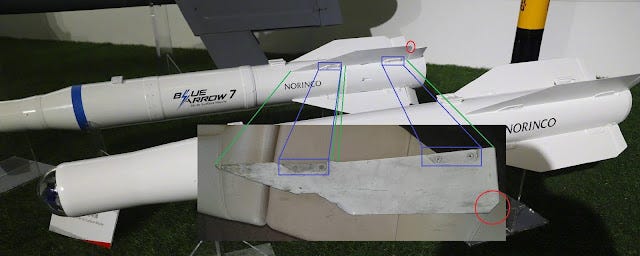

The Blue Arrow 7 missile is an air-to-surface export version of an anti-tank missile developed by Chinese arms company Norinco. It’s typically fired from a Wing Loong drone and can be used against troops or light vehicles with devastating effects.

Over the past few years, China has sent huge quantities of these missiles to Middle Eastern buyers like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. These missile sales often go hand-in-hand with sales of Wing Loong drones to the same buyers.

In the aftermath of many Blue Arrow 7 strikes - whether in Yemen, Libya, or, as we’ll see today, Western Sahara - three parts of the missile typically survive the blast.

From top to bottom in the picture above, the pieces that typically survive are: the rear casing, the tail fins, and the motor tailpipe.

The Rear Casing

First (and clearest) is the rear casing. As nice as the picture above may be, Blue Arrow 7 missile parts do not look quite as pristine post-explosion. Instead, they look a little more like this:

These images, surfaced by open source blogger AeroHisto, show Blue Arrow 7 missile parts found after strikes in Libya in 2019. The top image shows the missile’s pin mechanism, circled in blue, which is used to fasten the missile to the rail on the drone from which it is launched. The bottom image shows the pin frame, circled in red, which holds the pin in place and attaches the missile to the drone. It also shows an exhaust vent of some sort circled in green.

In the image below, taken shortly after a drone strike in Western Sahara, the pin, pin frame, and exhaust vents are clear as can be.

Metal pieces picked up by men arriving at the site of a drone strike in Western Sahara on November 14 also appear to be parts of the Blue Arrow 7 missile casing. However, there are not quite enough identifying details in photos or videos of that strike to definitively prove it was caused by a Blue Arrow 7, even though it seems probable.

The Tail Fins

Next up are the tail fins. Similarly, AeroHisto points out identifying details of post-blast Blue Arrow 7 missiles fired in Libya in 2019 here:

The same details were identified in BBC Africa Eye’s Game of Drones documentary, which laid the blame for a drone strike in Libya on a Blue Arrow 7 fired from an Emirati drone. (The pin, pin frame, and exhaust valves are also visible below2.)

In the animation above, pay particular attention to the fin’s beveled corners and the two sets of two slotted screws that hold each fin to the missile’s rear casing. As before, debris found in the wake of strikes in Western Sahara exhibit these same characteristics. These metal shards collected after a strike in al-Zalaa on August 26 match the fin design of the Blue Arrow 7.

The Motor Tailpipe

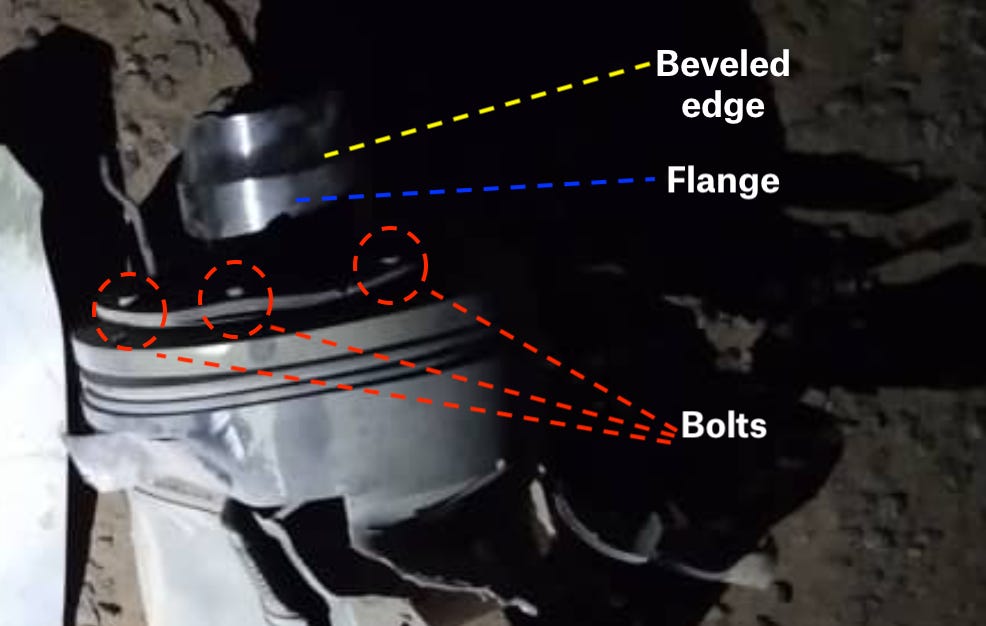

Finally, the Blue Arrow 7’s motor tailpipe has a few distinctive features that correspond to parts of debris found in at least two strikes in Western Sahara: the aforementioned August 26 strike in al-Zalaa and a November 3 strike that targeted Algerian trucks in Bir Lahlou.

The tailpipe assembly has at least three bolts (and likely more that are blocked by the angle of the image below) and a flange with a beveled edge that connects the tailpipe to the motor body itself. On the other end, there is another flange ring, perhaps to help connect the tailpipe to the missile’s rear end.

The three bolts, beveled edge, and one flange are visible on the motor tailpipe fragment found after the strike on August 26.

After the other strike, on November 33, all of the features are visible (also note that there are four bolts visible, rather than three, because none are blocked by the motor body or angle of the image).

In Conclusion…

Evidence shows Morocco used Blue Arrow 7 missiles to launch strikes on August 26, November 3, and likely November 14 as well. However, local news reports have compiled many, many more drone strikes in the region, indicating that the overall number of Blue Arrow 7 strikes may be substantially higher than the ones outlined here.

In a grim, final development, reports surfaced on November 20 of the first combat use of Turkish MAM-L missiles in Western Sahara.

Though Morocco says their strikes are justified within the context of their fight against the Polisario, others argue that these strikes have targeted Algerian and Sahrawi civilians, killing and injuring dozens and destroying numerous private and commercial vehicles.

With the conflict in Western Sahara entering a new, more intense phase over the past summer and fall, it is sadly likely that these strikes will continue. Whether with Turkish or Chinese-made missiles, it unfortunately looks like the trend of Morocco using drones to target Polisario fighters (and possibly civilians) is here to stay.

And, to a lesser extent, the Polisario’s Algerian supporters.

note on the image from menadefense this is a hydraulic suspension from the truck not a tailpipe