Making Radio Waves

Using radio intercepts to track a Russian ship sailing around northern Europe

Highlights from today’s post:

Unique applications of Morse code and online radios

Maps, lots of maps

The voyage of a certain Russian hydrographic ship in late fall

This week's edition is sponsored by OpenCage who operate a highly available, simple to use, worldwide, geocoding API based on open data. Try the API now on the OpenCage demo page.

In mid-November, an enormous Russian hydrographic ship sailed out of Danish waters into the chilly North Sea. The ship, the Admiral Vladimirsky, had turned her transponder off and was thus invisible to ship trackers. Most ship trackers, that is.

A group of radio hobbyists, however, diligently collected the weather broadcasts the ship sent back to Russian Navy headquarters. Contained in those reports was enough information to deduce the ship’s positions. Now, for the first time, we can string together all of the ship’s position reports into a coherent narrative of the ship’s journey.

But first, we need some background.

Within the wide spectrum1 of amateur radio listeners are a subset of people interested in what’s known as CW — Continuous Wave — transmissions. For the purposes of this article, CW basically means messages sent in Morse code.

While radio technology has largely moved beyond the need for the simplicity and high signal-to-noise ratio of CW/Morse code, it persists in certain applications. In addition to ham radio operators calling each other, it’s used by certain types of navigational beacons to exchange identifying information. It’s also used by ships and shore stations to send and receive weather messages over extremely long distances.

One radio frequency, 8345 kHz, is often used by the Russian Baltic Sea fleet to send and receive CW transmissions from naval headquarters in Moscow and other Russian bases. Using a software defined radio2 — and with the right timing, knowledge of Morse code, and a bit of luck — users can tune into this frequency and hear the messages sent between the ships and shore.

While there are a few types of messages sent on this frequency, weather reports contain the most information. While the majority of each weather message is fairly technical, containing details about sea state, salinity, cloud cover, and so on, each message also includes information about the ship’s location, speed, and heading3. The transmissions are sent to headquarters a few times per day and therefore provide ample opportunities to track the positions of these ships.

In fact, two of these radio watchers, TJ (@te3ej) and Nils (@DO6AN)4, caught reports on 8345 kHz from five separate Russian vessels spread over thousands of miles, from locations as varied as the coast of Spain, the English Channel, and Novaya Zemlya, Russia (though the majority were from the North Sea and Baltic Sea).

Let’s dial in on the Admiral Vladimirsky, which goes by the callsign RMIK. TJ and Nils recorded nearly 40 position and weather reports from the ship between early November and early December.

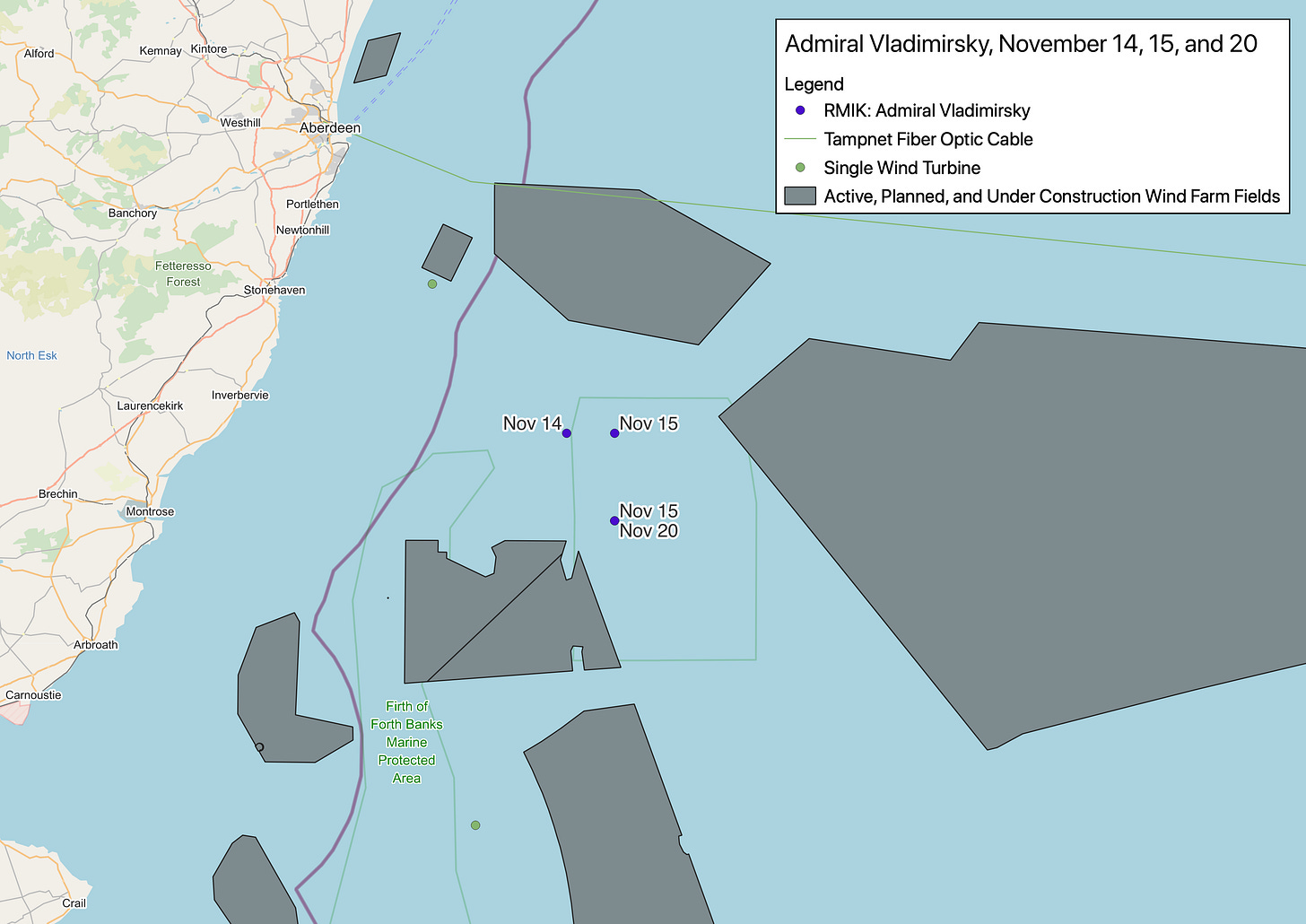

The ship took a fairly odd route from the Baltic to the North Sea. First, it spent a few days in the Moray Firth5 before sailing south to the waters outside Aberdeen and Dundee, Scotland.

There, it spent some time in the Firth of Forth Banks Marine Protected Area before heading south to the English Channel. It then took a long, looping path back up north and reported the same exact position on November 20 that it did on November 15 (hence the two date labels corresponding to the same dot on the map above).

We can make some guesses as to what the Admiral Vladimirsky was doing there. It wasn’t too far from a fiber optic cable running between Scotland, England, and southern Norway. It was also located smack in the middle of several current and future wind farm projects. Perhaps it was taking a closer look at one of these pieces of infrastructure?

A blogger speculated that the ship may have been keeping an eye on the Royal Navy’s HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier, which was in the area preparing for exercises in the North Atlantic. There may be some truth to this as well, since the Daily Express6 said the Admiral Vladimirsky was surveilling the Royal Navy's autonomous underwater vessels and other "electronic signatures" in the area.

And finally, it’s worth mentioning that Admiral Vladimirsky was located in an area of extremely rich geological and biological diversity, so it theoretically could have been doing actual scientific research as well.

Either way, after November 20, the ship swung east and took a standard route through Skaggerak and the Great Belt before heading northeast into the Baltic Sea on November 26.

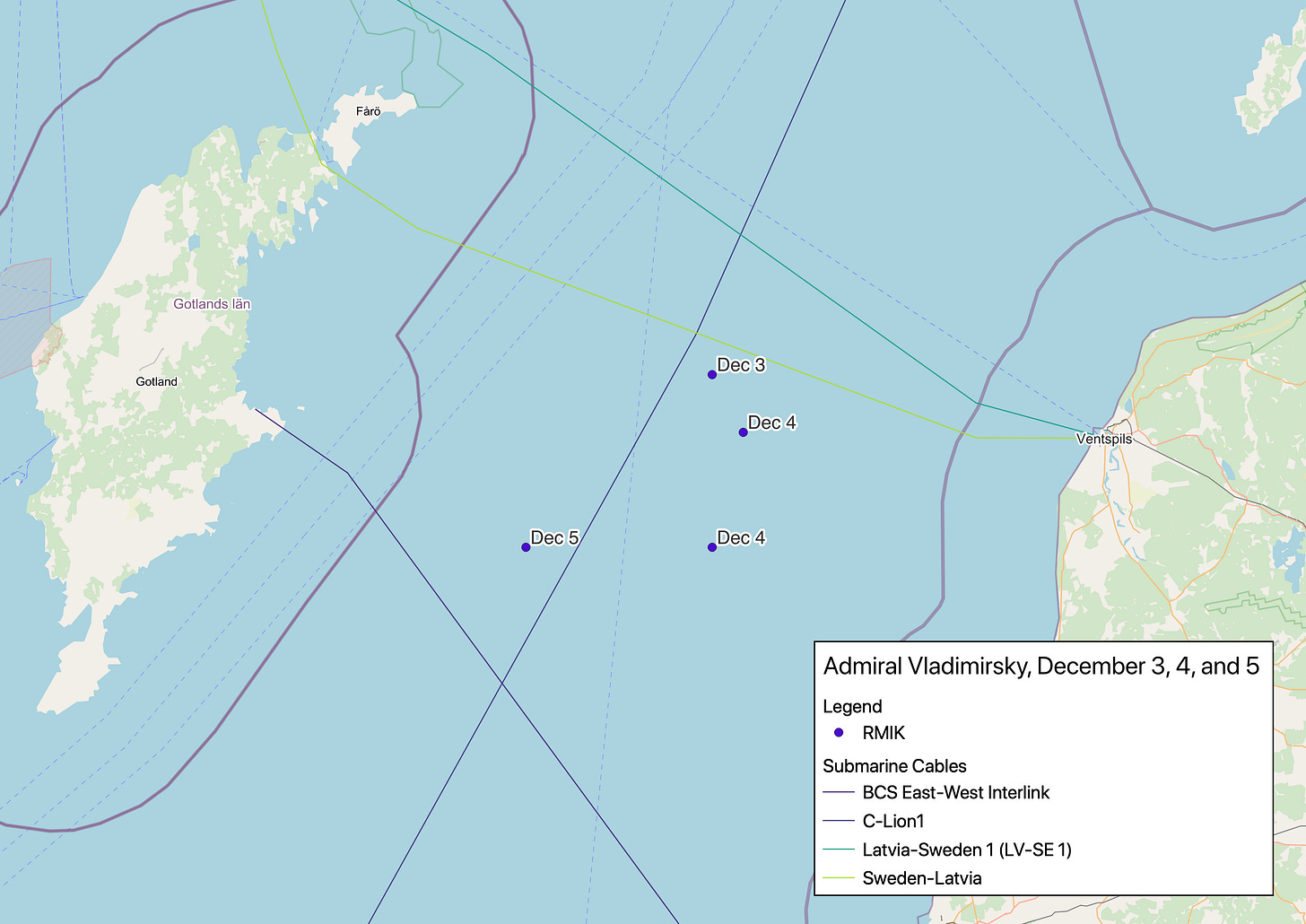

It disappeared from the radio for a few days before reappearing in the straits between Sweden and Latvia. Again, it appeared to loiter in an area filled with submarine cables between December 3 and December 5.

From there, it may have continued its mission or it may have returned to one of Russia’s naval bases in the Baltic at Kronstadt or Baltiysk. Unfortunately, its weather transmissions on 8345 kHz ceased.

While Nils and TJ lost track of Admiral Vladimirsky after December 5, they still managed to capture dozens of weather reports sent by the ship. Ever cooler, the skills and technology needed to do catch these broadcasts — and many others — are free and readily available to anyone with an internet connection. If you find anything interesting during your own explorations of the radio spectrum, please reach out!

Get it? Spectrum? Electromagnetic spectrum? I’ll see myself out.

Essentially just a radio one can tune into and receive messages on online. One of the better known SDRs can be found here.

If you want to learn more about how to decode the weather messages yourself, check out this link that explains the format in great detail.

Enormous thank you to TJ and Nils for patiently answering my questions, offering suggestions, and allowing me to use their work in this post!

Not pictured on the map above because TJ and Nils didn’t catch any position reports from that location.

Kind of tabloid-y, so grain of salt definitely needed.

One radio frequency, 8345 kHz, is often used by the Russian Baltic Sea fleet to send and receive CW transmissions from naval headquarters in Moscow and other Russian bases. Using a software defined radio2 — and with the right timing, knowledge of Morse code, and a bit of luck — users can tune into this frequency and hear the messages sent between the ships and shore. Bro thats so cool