Like many Americans, I was transfixed by the rapid pullout of US forces from Afghanistan and the even more rapid fall of the country to the Taliban. Amid all this news, I was particularly struck by what the Taliban spokesmen themselves were saying about their blitzkrieg through the Afghan countryside.

The Taliban have two military spokesmen: Zabihullah Mujahid, responsible for most of the country, and Qari Yousef Ahmadi, responsible for the Taliban’s traditional heartland of Kandahar, Helmand, and southwest Afghanistan.

The Taliban have a number of other spokesmen (they’re all men) who deal with international media, multimedia, the Taliban websites, political developments, and so on, but I chose to focus exclusively on their military spokesmen in order to track what the group was saying during its campaign to retake Afghanistan.

There has been some attention paid recently to how the Taliban have rapidly professionalized their public relations machine. But most articles have focused on specific images or storylines, rather than the group’s PR in aggregate. By applying some open-source data and basic analysis to the Taliban’s social media presence, I hope to provide a better sense of the long-running, strategic, and well-executed public messaging campaign the Taliban waged.

First, I scraped all of Zabihullah Mujahid and Qari Yousef Ahmadi’s tweets since April 13, 2021 (the date President Biden announced the withdrawal of the remaining US troops from Afghanistan) using Twint, an absolutely invaluable Python tool. Twint scrapes tweets, replies, follows, and basically any other public data you can think of from Twitter, while avoiding most of the limits imposed by Twitter’s API.

I stored the resulting tweet repositories in .csv files, opened them in Google Sheets, and dove into the analysis.

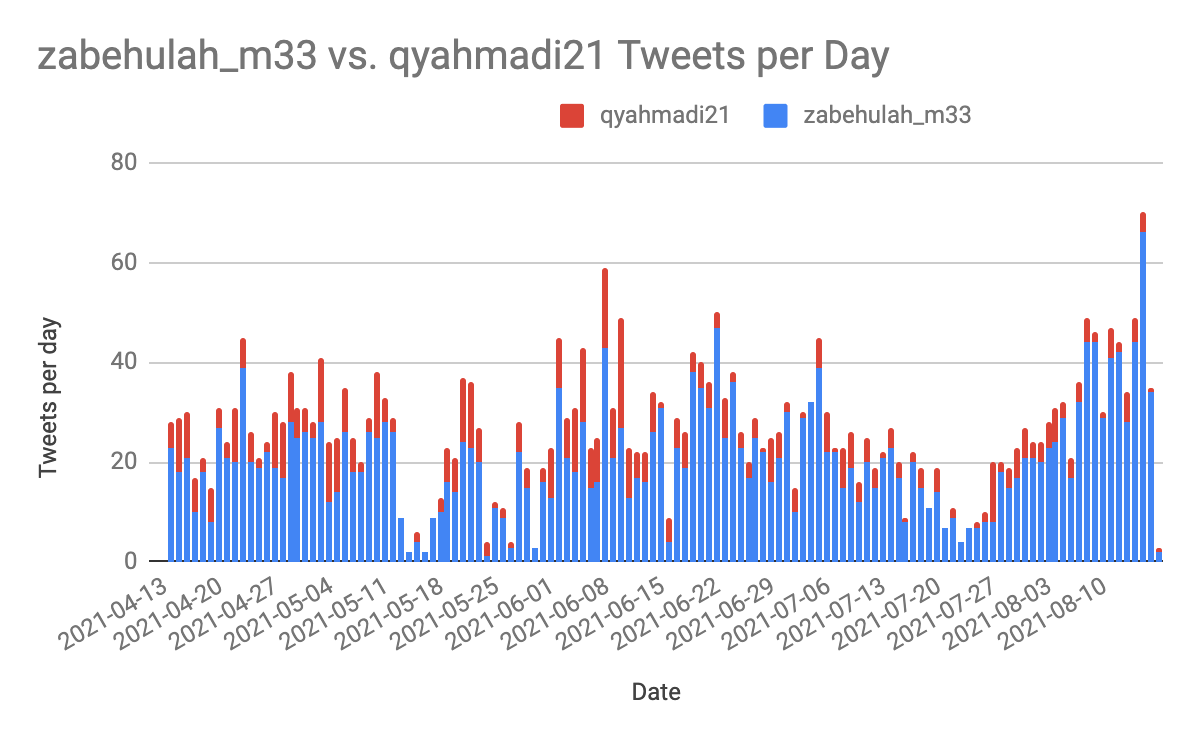

First, the overall volume of Taliban tweets fluctuated significantly since April, from a low of two tweets on May 13 to a high of 70 tweets on August 14. Zabihullah Mujahid (in blue, below) also tweeted much more often than Qari Yousef Ahmadi (in red).

The volume graph shows there were three distinct stages of the Taliban’s post-April 13 messaging strategy. First, there was business as usual between April 13 and mid-May. The group mixed political statements, claims of attacks across Afghanistan, and allegations of Afghan and US war crimes in roughly equal proportions, just as they always have.

The next stage, which ran from May 13 (the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Fitr) to late July, focused on the treachery, wickedness, and corruption of the US and Afghan governments while extolling the supposed virtues of the Taliban’s fighters. During the three-day Eid ceasefire, the group was mostly silent, except for accusing the government of breaking the ceasefire or killing civilians. They maintained that pattern of fewer attack claims and more accusations of war crimes until late July.

The third and final stage, from late July until the fall of Kabul on August 15, was far more martial than the previous two stages. The group claimed hundreds of attacks in rural areas and on the outskirts of major cities before claiming to take control of the cities themselves during the final week before the Afghan government collapsed.

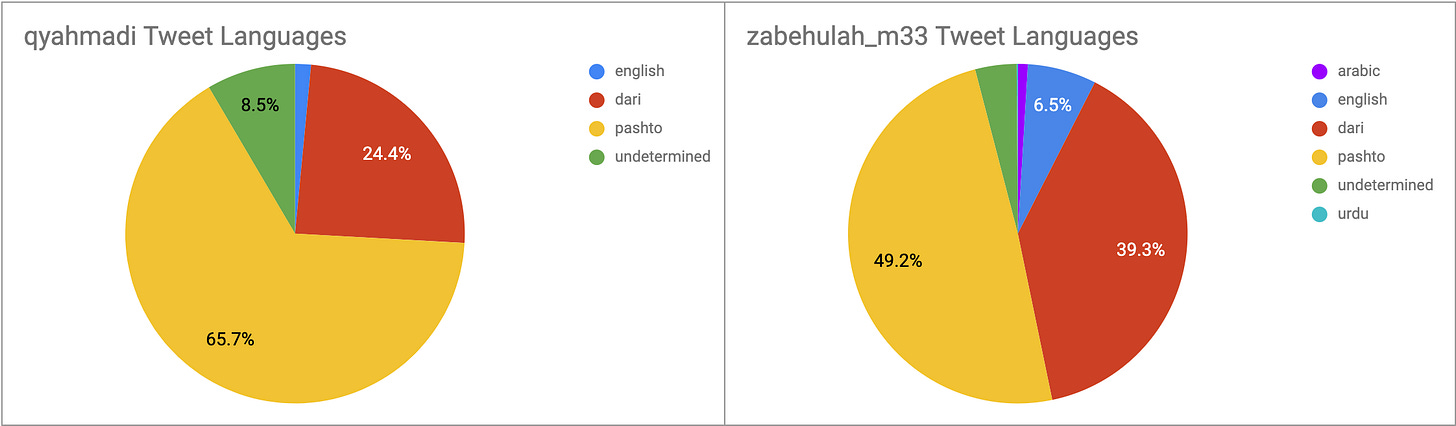

In doing so, the Taliban tailored their messages to their audience. Each spokesman had their remit and they stuck to it. Qari Yousef Ahmadi, shakier in his command of English and responsible for the Pashto-speaking regions of southwestern Afghanistan, tweeted mostly in Pashto. He usually only switched to Dari when he had to discuss events in Dari-speaking areas near the Iranian border1.

Zabihullah Mujahid, on the other hand, was downright cosmopolitan (by Taliban standards). He tweeted in Pashto less than 50% of the time and mixed in Arabic, English, and Urdu, not to mention a more significant proportion of Dari, which is spoken by much of northern and central Afghanistan.

Moreover (and this is where things get really interesting), the Taliban actually changed their message depending on the languages they used and, by extension, depending on who exactly they were targeting with their social media strategy. Hashtag analysis shows that the content published by the group varied widely based on the targeted audience.

In Dari and Pashto, the main languages of Afghanistan, the spokesmen’s posts largely focused on the Taliban’s strength and honesty. They wanted to show their ability to take on and defeat the Afghan and NATO armies while governing peacefully in areas they control. They also wanted to present themselves as a genuine alternative to the Afghan government, which is why, for instance, they posted so many pictures of them welcoming and socializing with Afghan security forces who surrendered to the group. Here, Zabihullah Mujahid celebrates an Afghan soldier from the Farah Province airport who turned himself into the Taliban along with a vehicle and several weapons:

The Taliban’s English content, however, focused on allegations of war crimes committed by US and Afghan forces. It was aimed squarely at the English-speaking people who would care about these allegations: journalists, NGOs, policymakers, and the Western public. The Taliban knew that the New York Times or AP might not cover a Taliban claim of a minor attack on an Afghan police checkpoint in a remote mountain valley, but they may investigate Taliban allegations that the Afghan Air Force bombed a school or that CIA-trained militia fighters shot up a village or that the US military blew up a hospital. For instance, here Zabihullah Mujahid posted a translation of a Pashto tweet in which he accuses US and Afghan forces of bombing a market in Lashkar Gah.

In the chart below, the Taliban’s most used English hashtags are primarily war crime accusations from various provinces like Baghlan or Laghman. But their most common Dari and Pashto hashtag is “alfath”, which is used for sharing details about the Taliban’s military campaigns2. That hashtag was used almost five times more often than their next most used Dari and Pashto hashtag, indicating that, in local Afghan languages, the group popularized their military exploits, but in English, they drummed up global attention for atrocities committed against Afghans.

But how do we know the Taliban’s social media strategy was effective? (aside from the fact that they won the war). Well, like any savvy social media campaign, their engagement went up!

Twitter users engaged with their content far more toward the end of the Taliban’s campaign than at the beginning. Engagement was particularly high during the last month or so before the fall of the Afghan government. These likes and retweets show that more people saw their posts and therefore heard about the impending conquest of the country from the Taliban.

The possible implications of the Taliban’s successful PR campaign are tantalizing. Obviously, the Taliban won the war. But did more recruits join the group thanks to their messaging strategy? Did the Taliban’s claims of being a powerful, incorruptible force allow them to cut deals with Afghan security forces rather than fight them? Did Ahmadi and Mujahid’s English tweets undercut the US and Afghan governments’ narrative that the Afghan government was winning the war? Ultimately, was the group’s PR strategy a more effective weapon than their physical arsenal? All are plausible outcomes that merit further study.

But for now, it’s at least clear that the Taliban implemented a coherent, multifaceted social media campaign as part of their strategy to take over Afghanistan. From a PR perspective, that campaign was a runaway success, with not only tens of thousands of likes and retweets but a newly-conquered country to show for it.

For instance, he claimed several attacks from Herat and Farah in Dari.

Note: “alfath” is the Google translation of the Taliban’s “Al-Fateh Jihadi Operations” campaign, launched in 2019. Any tweet including #alfath in any language essentially refers to military operations conducted by the Taliban.