Tracking Sentinel-1 Interference in Kashmir

A Mostly Unsuccessful Endeavor

It’s been a bit since my last post - I’m working on a more developed investigation that will take take some time to research and write. In the meantime, I have a quick piece on Kashmir to share with you all today. I know recent posts have been Kashmir-heavy - guess it’s just been a South Asian autumn, as far as my open source investigations are concerned. Onward!

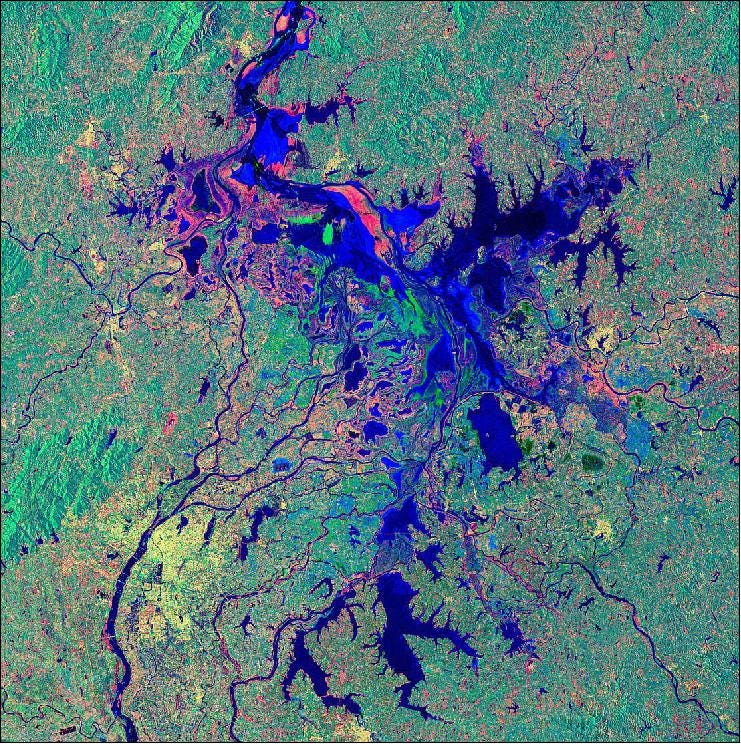

Recently, I’ve been playing around with satellite imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 mission. This imagery is what’s known as Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery. SAR imaging satellites essentially shoot out a beam of radar waves and use onboard sensors to capture and interpret the waves that bounce back from the ground. These data are then transmitted back to earth in the form of occasionally trippy and often astonishingly beautiful pictures:

China’s Poyang Lake as seen by Sentinel-1 satellites in 2016. Credit: eoportal.org

Significantly (for our purposes at least), Sentinel-1 satellites fire off their radar waves in the C-band of radar frequencies, with a central frequency of 5.405 GHz. In addition to forming information-packed and visually appealing images, Sentinel-1’s radar waves will also interfere with the waves of ground radars that also transmit in the C-band. These interference zones appear as bright scars across the imagery, as laid out in this incredibly informative piece by Harel Dan.

But which C-band ground radars actually interfere with Sentinel-1 satellites? The answer - (certain) military radars. Dan and other open-source wizards have pinpointed a few systems that can cause Sentinel-1 interference, including the Turkish Koral electronic warfare system and the system used by US Patriot missile batteries, the AN/MPQ-53/65 radar.

While panning over Kashmir with the European Space Agency’s user-friendly Sentinel Hub EO browser, I noticed a few images that showed extremely strong C-band interference. For example:

As far as I knew, neither India nor Pakistan use the radar systems that are known to cause C-band interference. So what could be at the root of this bright swath across the image?

I did some research and found that although Pakistan does not operate any C-band radars, India does. Several years ago, India’s secretive DRDO military research agency piloted a new weapon-spotting radar - the Swathi. Its frequency is between 4 and 8 GHz, which places it right around Sentinel-1’s interference-causing frequency of 5.405 GHz.

Even more promising, Indian military brass confirmed that the radar is deployed along the Kashmir Line of Control to spot incoming artillery rounds from Pakistan and improve the accuracy of India’s outgoing fire. To me, this all but confirmed that the interference scars shown on the Sentinel-1 imagery were caused by Swathi radars.

With the wind in my sails and a pep in my step, I was looking forward to replicating Dan’s process for Kashmir and determining exactly when and where the Swathi radars were deployed.

I was (mostly) unsuccessful.

Despite identifying three distinct areas of Sentinel-1 interference likely caused by the Swathi weapon-spotting radar in Kashmir over the past year (below), I was unable to precisely geolocate a single radar system in the region.

The effort wasn’t a complete failure, however, as the imagery did reveal some interesting patterns and allowed me to make some educated guesses about the radar system.

For one, unlike the interferences from the Patriot missile batteries revealed in Dan’s article, which were essentially constant regardless of which day, time, or imagery resolution you searched for, the interferences in the Kashmir imagery only popped up once or twice per location, only to disappear again.

This here-today-gone-tomorrow interference is frustrating but understandable given the specifications of the Swathi system. The radar is highly mobile, as it is mounted on two trucks, allowing it to rush forward when required, and retreat to safer areas when it is not needed. The DRDO even developed a smaller, more rugged Mark II version specifically for use in mountainous Kashmir that improves on the mobility of the Mark I:

As I said above, I couldn’t find a single radar system in Kashmir on Google Earth’s satellite imagery. But I still couldn’t let it go - where were these radars stationed? So, just for fun, I tried to predict where under the interference scars these radar units were actually located. I scoured Google Earth for possible locations and found a few interesting candidates for each area of interference.

For the northernmost scar, detected on September 10, 2020, a military airport and adjacent base in Poonch, Kashmir lie directly under the middle of the interference band. The same day, news sites published reports about Pakistani artillery shelling the nearby Mankote, Degwar, and Mendhar areas. My speculation is that the radar was moved to Poonch airport and activated to detect, track, and respond to the Pakistani shells falling across the Indian side of the border.

Even if it wasn’t located at the airport itself, the Poonch region is ringed with Indian fortifications and artillery batteries, any of which could have hosted a Swathi system for a few days.

Poonch airfield and adjoining military base.

Poonch Airfield is directly underneath the September 10 interference scar and the three areas targeted by Pakistan on the same day are well within the Swathi radar’s 50 kilometer range.

For the middle scar, this time detected on September 4, 2019, I found a few Indian helicopter landing pads and a support base in the middle of the C-band interference strip. On that day, no shelling was detected within the radius of the radar’s 50 kilometer range. However, in early September, Indian news networks published reports that Pakistan had sent an additional brigade, or 2,000 troops, to Kotli, which is just north of the helicopter pads on the Pakistani side of the border. Perhaps it’s just a coincidence or perhaps the Swathi radars were at the base in case the new Pakistani troops attempted to shell the Indian side of Kashmir.

Helicopter landing pads and small adjoining support base.

Kotli is seen here inside the Swathi radar’s range, assuming the radar was stationed at the helicopter pads.

Finally, the southernmost scar, which was detected by Sentinel-1 imagery on September 22, 2020, follows the pattern of the first two interference bands. This time, I found a sizable Indian field artillery base directly underneath the interference band. Pakistani shelling also targeted a location close to the base the day before the image was taken and Indian forces detected a drone launched from Pakistan on September 22 as well. Since tensions in that region of Kashmir were already high, it would not surprise me if a Swathi radar unit was activated at or near the artillery base to both detect the Pakistani fire and direct India’s response.

Indian field artillery base - note six-cannon artillery battery, dozens of vehicles, and many support and logistics buildings.

Pakistani shelling targeted Sunderbani on September 21 and a Pakistani drone was detected in Akhnoor on September 22 - the same day this Sentinel-1 image was taken. Both are within the radar’s 50 kilometer range.

Although I wasn’t able to actually find the radar systems, an interesting pattern nonetheless emerged from the imagery. Sentinel-1 interference bands would appear over Indian military bases and airfields around the same time that Pakistani artillery strikes or other provocations occurred in the areas around the installations. Unfortunately, the one- or two-day clashes in each location meant that there was never enough time for a Sentinel-1 satellite to re-image the interference area before the Swathi radar system scooted back out of the danger zone after the clashes ended.

Again, as this is only my hypothesis, I’ll be on the lookout for future Sentinel-1 imagery to confirm or deny my guesses. Until then, let’s just hope things stay quiet in Kashmir…